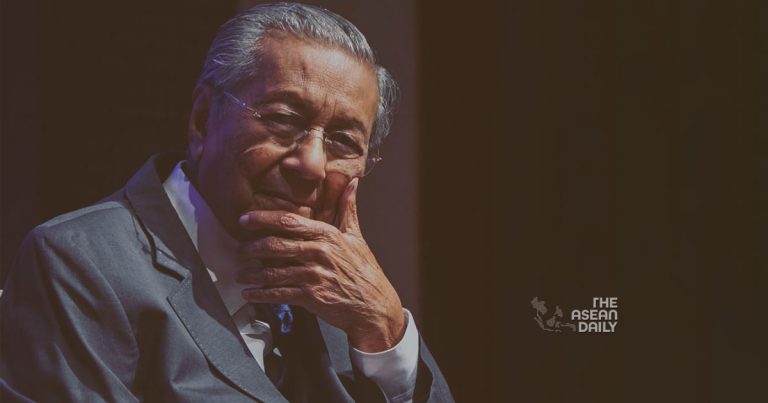

14-1-2024 (KUALA LUMPUR) Former premier Mahathir Mohamad’s recent remarks questioning the loyalty of Malaysian Chinese and Indians sparked heated debate over the country’s delicate multicultural fabric. But while divisive, his comments reflect deeper anxieties confronting Malaysia’s diverse society.

Mahathir essentially advocated total assimilation as the only path to equal belonging, arguing minorities cling to separate identities instead of adopting Malay language and customs. He implied dual national loyalties persist despite citizenship.

Of course, this “us versus them” rhetoric draws pushback for diminishing minorities’ contributions and rights. Critics argue the constitution enshrines practising faith and culture, with integration occurring organically over generations, not overnight.

But the backlash also risks missing underlying concerns driving assimilationist attitudes. Many Malays do genuinely feel the comity binding Malaysia’s disparate communities is fraying, even if minorities have national pride.

The issue requires viewing identity beyond legalistic debates over constitutions. Nationhood anywhere involves grappling with complex questions of history, emotions and relationships between citizen groups. Simply shouting down conservative views won’t build the psychological bonds vital for unity.

Malaysia emerged through a political contract between ethnic power blocs, not a single national identity predating statehood. Its three major groups – Malays, Chinese and Indians – had limited interaction under colonial divide-and-rule. British granting citizenship en masse before independence heightened tensions.

So nation-building since 1957 centred on balancing majority Bumiputera interests with minority rights, under an affirmative action framework some label apartheid. But policies entrenching differences also hindered organic unification, allowing distrust to fester.

With threats to group status perceived existential, discussions on identity turned combustible. Assimilation notions reflect fears of being politically and economically overwhelmed in one’s own homeland.

Yet enforcing uniformity only breeds resentment, as minorities unwillingly shed cherished traditions and language. Embracing diversity makes assimilation voluntary by fostering inclusion and social mobility, reducing insularity over time.

Myanmar offers cautionary lessons on cultural subjugation. Forced ‘Burmanisation’ of minorities helped stoke decades of separatist revolts, hindering true reconciliation. Integration must evolve, not be imposed artificially.

That requires patiently strengthening identity rooted in shared institutions and experiences, beyond just pledging common citizenship. Rituals like national service present opportunities to bridge ethnic and religious divides at the societal level.

Also essential is ensuring economic development and political representation benefit all communities, alleviating zero-sum contests for resources that fragment the nation. needs transcending racial lenses.

Leaders play a pivotal role in shaping discourse that either divides or unites. Malaysia’s history is undeniably multicultural; identity debates should celebrate this richness. Younger generations especially appreciate the dynamism diversity brings when harnessed constructively.

But lasting change requires going beyond elite platitudes extolling fuzzy ‘unity’. Serious reflection is needed on why minority integration remains a worry despite official nationhood. The past offers cultural touchpoints to reinvent Malaysian identity for the future.

Neither forced assimilation nor inertia are constructive options. Real unity comes from removing barriers to minorities embracing a common national identity without shedding their ethnic identities. Malaysian nationalism must make all feel valued stakeholders, not second-class citizens.