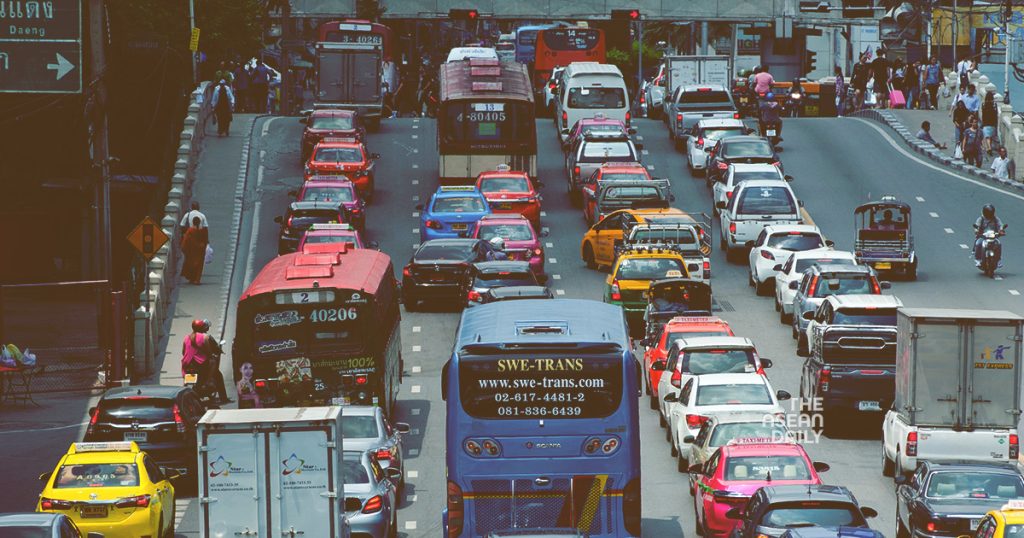

20-5-2023 (Jakarta) Traffic congestion remains a major problem in Southeast Asia’s major cities, including Jakarta, Bangkok, and Kuala Lumpur. The reason for this is the absence of other good options, with private vehicle ownership increasingly trumping residency numbers. Experts have proposed solutions, ranging from the rudimentary, such as carpooling, to the bureaucratically complex like congestion charges, but they say no panacea exists. An approach of small incremental steps building towards a long-term goal represents the cities’ best bet, although just as fundamental is the “political will” of local authorities, said Singapore-based transport economist Walter Theseira.

According to an annual global traffic index by navigation specialists TomTom, Jakarta was the 29th most congested city out of 390 surveyed in 2022, ninth out of 35 in Asia, and second behind Manila in Southeast Asia. Bangkok placed 15th and Kuala Lumpur 22nd in the continent. With some of these cities only lifting all COVID-19 activity restrictions at the end of last year, they could place even higher in the yet-to-be-released 2023 index, which rates cities by their travel speeds, fuel costs, and CO2 emissions.

Relentless traffic also contributes to pollution, with Jakarta having only two days in all of 2019 when air quality was deemed “healthy.” Driving in stop-start traffic is stressful and can lead to recklessness, road rage, and accidents, which also have a toll on mental health. For some, the biggest cost of all remains that precious asset of time. People in Jakarta spent 214 hours in rush-hour traffic last year, while those in Bangkok were occupied for 192 hours and in Kuala Lumpur, 159 hours.

A preference for one’s own set of wheels is clear across regional cities, where private vehicle ownership increasingly trumps residency numbers. That’s 11.7 million machines to about 11 million people in Bangkok and its surrounding urban region, and 9.85 million versus 9 million in the Klang Valley area covering Kuala Lumpur and adjacent areas. Jakarta and its wider metropolitan area are occupied by 20.7 million vehicles to 13.5 million people. They are helped by relatively low prices and little or no restrictions placed on owning and using a private vehicle, whether new or handed down. An abundance of cheap parking space also encourages more vehicles, more driving, and, therefore, more congested roads.

Poor first and last-mile connectivity, inconvenience, and high costs in some cases have led to residents shunning public transport in the major cities across Southeast Asia. This is despite attempts since the 1990s to develop multiple rail and bus networks, which analysts say remain inadequate and unreliable.

Effective management of cities with such high density and activity levels would mean deprioritizing roads when it comes to developing travel options. High on the list would be other modes of transport that can accommodate a large number of people, such as electric mass transit railway systems and buses. Building more roads and expressways is hardly the answer, as it only compounds the problem.

The Economic Cost of Congestion

The economic cost of congestion is significant. Studies estimate that the region loses approximately two to five percent of gross domestic product (GDP) due to heavy traffic. Metro Manila is considered to have the worst traffic, which is equivalent to an estimated daily economic loss of ₱3.5 billion (US$67 million). With the rising number of vehicles in the region, the situation could worsen to ₱5.4 billion a day by 2035 if no steps are taken to intervene.

The ‘last kilometre’ problem is also exacerbating the issue. Commuters face challenges with the journey from metro stations to their final destinations, with essential integration between rail systems and other modes of transport being underdeveloped. The region is undersupplied with public transportation, with Jakarta and Manila’s combined urban rail network amounting to just 100 kilometres, which leaves commuters exposed to heat, humidity, rain, flooding, and other elements.

Solutions to Traffic Congestion

To address traffic congestion in Southeast Asian cities, experts have proposed a range of solutions, all of which require the “political will” of local authorities. An approach of small incremental steps building towards a long-term goal represents the cities’ best bet. This includes prioritizing other modes of transport that can accommodate a large number of people, such as electric mass transit railway systems and buses. Effective management of cities with high density and activity levels also means deprioritizing roads when it comes to developing travel options.

One possible solution is congestion charges, which have been proposed in Jakarta and Bangkok. However, implementing such charges could be challenging due to pushback from various stakeholders and concerns about cost and impact on taxes.

Assoc Prof Theseira warns that efforts to improve public transport will come at a substantial cost and could potentially impact taxes. A project such as an MRT subway could significantly redistribute land values and create “a lot of incentive to distort planning and alignment,” he said.

Cities are better off considering a graduated, step-by-step approach, said experts. Governments could invest in a new rail system to bring up commuter capacity, then encourage its use by tightening parking or bringing in tolls – with the aim of shifting mindsets, behaviour, transport patterns and land use away from private vehicles.

While congestion charges have been proposed in some cities, they could be challenging to implement due to pushback from various stakeholders and concerns about cost and impact on taxes. Assoc Prof Theseira warns that efforts to improve public transport will come at a substantial cost and could potentially impact taxes. A project such as an MRT subway could significantly redistribute land values and create “a lot of incentive to distort planning and alignment.” Graduated, step-by-step approaches are therefore recommended to avoid unrealistic, myopic goals that cannot be met with available resources.

Investing public transport is crucial to reducing traffic congestion in Southeast Asia’s major cities. This could involve developing multiple rail and bus networks, promoting alternative modes of transportation, and improving pedestrian access. However, these measures have had limited success due to poor first and last-mile connectivity, inconvenience, and high costs. The region is undersupplied with public transportation, with Jakarta and Manila’s combined urban rail network amounting to just 100 kilometers.

The preference for one’s own set of wheels is clear across regional cities, where private vehicle ownership increasingly trumps residency numbers. This is despite attempts since the 1990s to develop multiple rail and bus networks, which analysts say remain inadequate and unreliable. Poor urban planning has failed to keep pace with cities’ urbanization and population growth, leading to a scarcity of land and housing areas spilling into the suburbs.

The economic cost of congestion is significant, with studies estimating that the region loses approximately two to five percent of gross domestic product (GDP) due to heavy traffic. Metro Manila is considered to have the worst traffic, which is equivalent to an estimated daily economic loss of ₱3.5 billion (US$67 million). With the rising number of vehicles in the region, the situation could worsen to ₱5.4 billion a day by 2035 if no steps are taken to intervene

Cities must take measures to discourage private vehicle ownership and usage, such as increasing the cost of owning and using a vehicle. One suggestion is to use the additional revenue generated from increased expenses for private transport to support public transport. Another approach is for governments to invest in new rail systems to increase commuter capacity and encourage their use by implementing tighter parking regulations or tolls. The ultimate aim is to shift mindsets, behaviors, transport patterns, and land use away from private vehicles.

Although congestion charges have been proposed in some cities, their implementation could face opposition from various stakeholders and concerns about cost and tax impact. Assoc Prof Theseira cautions that improving public transportation will come at a significant cost and could potentially impact taxes. For instance, a project like an MRT subway could significantly redistribute land values and create incentives to distort planning and alignment. As such, it’s advisable to adopt graduated, step-by-step approaches to prevent unrealistic, myopic goals that cannot be achieved with available resources.