19-5-2024 (SINGAPORE) As Lawrence Wong assumes the premiership of Singapore, inheriting the reins from Lee Hsien Loong, one of the most pivotal aspects of his new role will be shepherding the nation’s intricate relationship with China. Lee, who will remain in the cabinet as a senior minister, identified bilateral ties with the Asian powerhouse as among the city-state’s most crucial during his farewell speech. This transition of leadership comes at a time when Singapore’s adroit management of its China ties has been put to the test amidst a rapidly evolving geopolitical landscape.

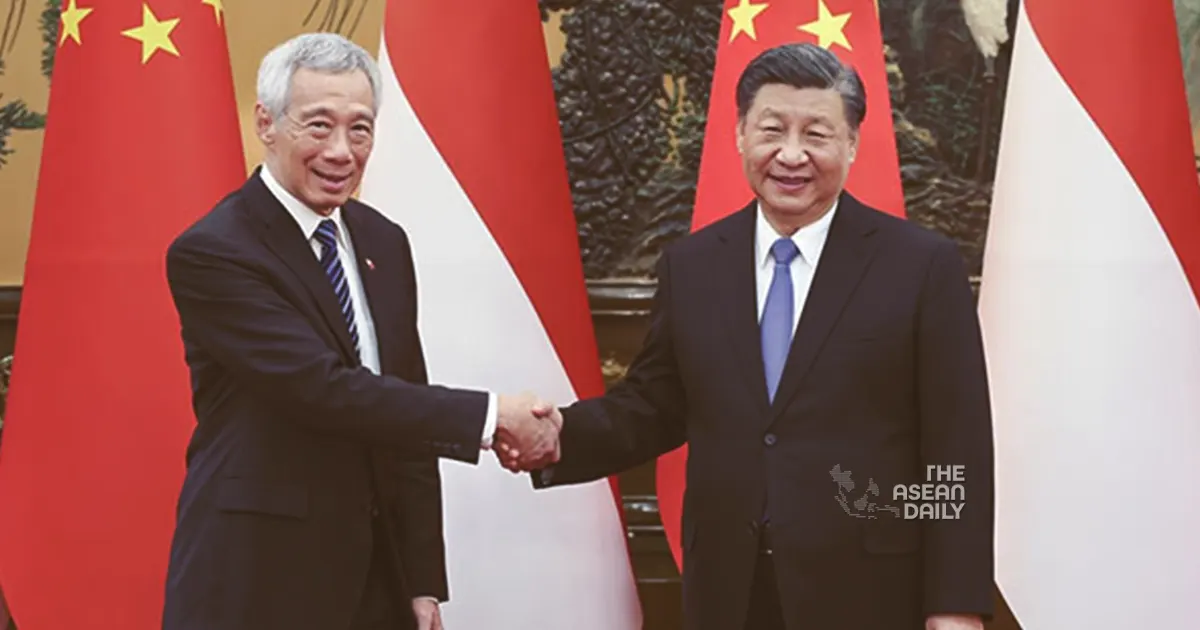

Lee’s tenure as prime minister spanned two distinct Chinese administrations – the more cautious approach of Hu Jintao from 2002 to 2012, and the discernibly more ambitious and sweeping foreign policy goals of Xi Jinping since 2012. Despite this marked shift, the enduring strength of the Singapore-China partnership, coupled with the government’s steady stewardship, has largely maintained stable bilateral relations – a testament to Lee’s legacy.

Major platforms bolstering Singapore-China cooperation were initiated and reinforced during Lee’s watch. The Joint Council for Bilateral Cooperation, established in 2003, provided an equal and high-level arena for regular dialogue, with Lee co-chairing the inaugural meeting in 2004 while still deputy prime minister. The Singapore-China Forum on Leadership (2009) and the Singapore-China Social Governance Forum (2012) were also launched under his leadership, fostering deeper engagement.

Lee’s rare distinction of speaking twice at the Central Party School of the Chinese Communist Party, in 2005 and 2012, further underscored the significance of the bilateral relationship during his premiership.

However, the ties were not without their hiccups. In 2004, Lee’s unofficial personal visit to Taiwan, shortly before assuming the premiership, drew a strong rebuke from mainland China, with warnings of potential consequences. The situation stabilised, and in October 2005, newly appointed Prime Minister Lee made a state visit to China at Premier Wen Jiabao’s invitation.

Addressing the contentious South China Sea issue at the 2016 National Day Rally, Lee articulated Singapore’s interests in upholding international law and ensuring freedom of overflight and navigation in the disputed waters – a stance that analysts suggested contributed to Beijing’s displeasure, culminating in the seizure of nine Singapore armoured vehicles by Hong Kong customs later that year.

Despite these challenges, Lee’s leadership heralded a closer economic and political relationship with China. In 2013, Singapore became the largest foreign direct investor in China, while China emerged as Singapore’s largest trading partner. The number of bilateral flagship projects rose to three under Lee, with the Tianjin Eco-city (2008) and the Chongqing Connectivity Initiative (2015) joining the Suzhou Industrial Park (1994). Bilateral relations were further elevated to an “all-round high-quality future-oriented partnership” in April 2022.

Yet, this deepening of ties was a gradual and carefully calibrated process. Remarkably, under Lee’s stewardship, Singapore’s relationship with the United States was also significantly strengthened, and the Singapore Armed Forces continued to train in Taiwan – a delicate balancing act amidst mounting pressure from both superpowers to take sides.

Singapore has largely charted its own course, maintaining meaningful cooperation with both China and the US, a feat acknowledged by Xi Jinping himself, who in 2023 described Singapore-China ties as a “model” for other countries. The city-state’s credibility and trust were further underscored when it hosted the 2015 summit between Xi and Taiwan’s then-leader Ma Ying-jeou.

Underpinning this success has been a concerted effort to highlight Singapore’s distinct multiculturalism in the face of Beijing’s attempts to claim proprietorship over peoples of Chinese ethnicity. Lee supported the construction of the Singapore Chinese Cultural Centre in 2012, serving as a counterpoint to the China Cultural Centre established by Beijing. During his 2022 National Day Rally, he underscored the unique Singaporean Chinese practices that had emerged, emphasising that “Chinese Singaporeans had sunk their roots here in Singapore” and were distinctly Singaporean.

These moves reflect a broader shift to improve foreign policy literacy, a priority that will likely remain under the new prime minister, informed by an acute sensitivity to Singapore’s multi-ethnic and multicultural fabric. As Lee himself stated, Singapore is not “a cat’s paw” for any other country, and cultural affinity to China should not be conflated with political loyalty.

While Lee’s critics have largely focused on domestic policies, his adept management of Singapore’s external affairs has been a hallmark of his tenure. His acumen in international affairs and ability to grasp complex global issues with a helicopter view are unparalleled, as exemplified by his prescient Foreign Affairs essay on “The Endangered Asian Century” in June 2020, which foreshadowed much of the current US-China competition and existential angst about the international order.

Yet, Lee also excelled in translating these global issues for the common Singaporean, carefully explaining the implications of US-China competition and the war in Ukraine during a parliamentary debate last year – a testament to his statesmanship.

As Wong assumes the mantle of leadership, he inherits a complex web of challenges and opportunities in Singapore-China relations. Potential risks include slower economic growth in mainland China, flashpoints in the Taiwan Strait and South China Sea, renewed endeavours to influence Singaporean society, or a sharp deterioration in US-China ties – all of which will test Wong’s foreign policy mettle.

At the same time, new opportunities will undoubtedly arise, and it falls upon the new prime minister and his team to seize these in service of the nation’s interests and the Singapore-China relationship.

As Wong himself alluded, old formulas and dicta may not suffice in today’s increasingly complex international environment. Is it enough, or even desirable, to simply “keep the ship steady” or maintain the status quo? Can there be greater public discourse on major foreign policy questions? Is there scope for fresh thinking about Singapore’s place in the world, while remaining clear-eyed about the limits of what it can achieve?

There are no obvious answers, but one thing is clear: Lee Hsien Loong has handed over the “China account” in remarkably good shape, replete with potential for further growth and development under the new leadership.