14-6-2024 (KUALA LUMPUR) The Malaysian government has been accused of intensifying its crackdown on dissenting voices on social media platforms, fueling concerns over the erosion of free speech and civil liberties in the country. According to recent reports, Malaysia submitted an unprecedented number of requests to TikTok, demanding the removal of content during the second half of 2023, a move that critics argue is aimed at silencing political opposition.

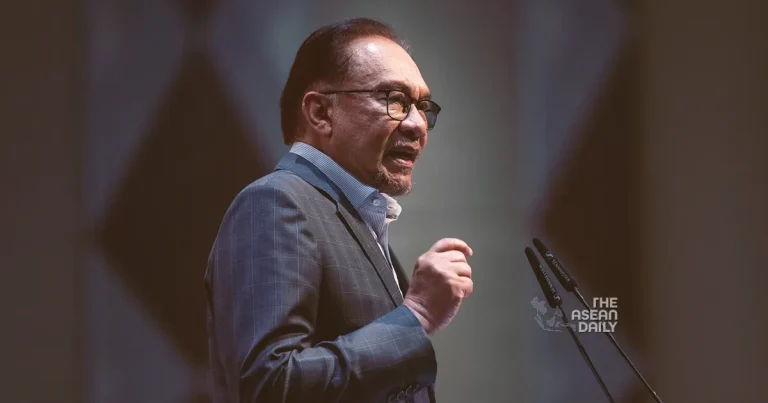

The latest biannual transparency report released by TikTok revealed that the Malaysian government made a staggering 1,862 requests for content takedowns between July and December 2023, marking a 5.5-fold increase from the previous six-month period. This figure, which amounts to an average of 10 daily requests, far surpassed the demands made by any other nation during the same period. Throughout 2023, Malaysia’s requests for content restrictions on TikTok skyrocketed to 2,202, a more than 30-fold surge compared to the 70 requests made in 2022. This escalation in censorship demands coincided with the return to power of Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim and his Pakatan Harapan (PH) coalition following the November 2022 general election.

While TikTok did not disclose the specific nature of the content targeted for removal, the platform stated that it would comply with requests if there were violations of community guidelines or local laws. However, critics have accused the government of exploiting this policy to suppress dissenting voices, particularly those affiliated with the opposition Perikatan Nasional (PN) alliance. PN’s success on TikTok, which was widely credited for its unexpected gains in the 2022 general election, has allegedly made it a prime target for the government’s censorship efforts. Wan Saiful Wan Jan, the shadow minister for communications, drew parallels between the current crackdown and the infamous Operation Lalang of 1987, when over 100 politicians and activists were arrested, and publishing licenses were revoked from several newspapers. “It’s a new Ops Lalang.

Anwar criticises what (then PM) Mahathir Mohamad did, but now he is doing worse,” Wan Saiful told The Straits Times. The trend of escalating content restrictions extended beyond TikTok, with Meta, the parent company of Facebook and Instagram, reporting that nearly 8,600 content restrictions were applied in Malaysia in 2023, a 15-fold increase from the previous year. This surge in takedown demands has fueled criticism that the multi-coalition “unity government” led by Anwar’s PH alliance, which has long campaigned on a reformist platform promising to broaden civil liberties, is now clamping down on free speech.

In May, Reporters Without Borders (RSF) released its 2024 World Press Freedom Index, which saw Malaysia plummet from 73rd place to 107th, citing frequent blockages of news sites critical of the government. Anwar dismissed the downgrade, claiming that his administration was merely taking a tough stance against “racists and religious bigots,” a response that drew flak from civil society organizations for misrepresenting the reasons behind the drop in rankings. Lawyers For Liberty (LFL) pointed to the website restrictions and the blocking of TikTok videos by government critics as the real basis for the RSF downgrade. “How can there be freedom of press when all criticism of the establishment is swept under the convenient category of 3R,” said LFL director Zaid Malek, referring to the administration’s claim of stamping out offensive rhetoric touching on the sensitive issues of race, religion, and royalty.

According to sources involved in social media monitoring, the demands for content restrictions are continuing to grow in 2024, with authorities dedicating personnel to trawl platforms for offensive material. “A vast majority are political in nature. Over 90 percent possibly,” said a person involved in the content restriction process. Meta’s transparency report for the second half of 2023 revealed that it restricted access in Malaysia to over 4,700 items reported by the Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission (MCMC), including content deemed as “hate speech based on religion,” “criticism of the government,” and “racially or religiously divisive content and bullying” under the controversial Communications and Multimedia Act (CMA).

Critics, including government MPs, have called for amendments to the CMA, arguing that its ambiguous wording opens the door to abuse and censorship. While the MCMC and Communications Minister Fahmi Fadzil did not respond to queries from The Straits Times regarding the takedown requests and claims of silencing dissent, Fahmi has repeatedly denied allegations of issuing orders to block websites or social media accounts. However, in March, Fahmi was embroiled in a heated debate with Wan Saiful and former education minister Radzi Jidin (PN) in Parliament over whether the latter’s TikTok videos on the shrinking value of the ringgit were “geofenced” to block Malaysians from viewing them. Fahmi refused to directly address the question, asserting that if there were no freedom of speech, their accounts would have been removed from all social media platforms.