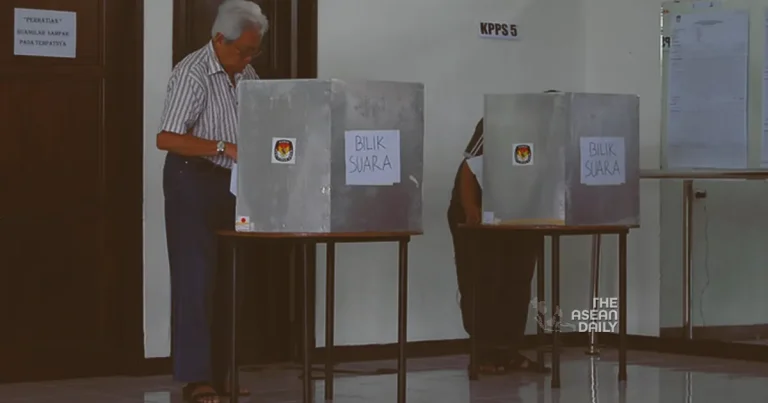

28-2-2024 (JAKARTA) The aftermath of Indonesia’s presidential and legislative elections on February 14 has left a grim toll on election workers, with 114 reported deaths and over 15,000 falling ill during the marathon event. The scale of the elections, deemed the world’s largest held in a single day, has prompted calls for reforms and changes to the election format.

Fahmi, an election worker from Bogor, West Java, shared his experience of a grueling 26-hour shift, uploading data until 8 am on February 15. While some workers had completed their tasks by dawn, the workload, exacerbated by the increased number of legislative candidates, proved overwhelming for many.

The deaths and illnesses among election workers are being labeled a “systemic problem” by Heroik Pratama, a researcher at the Association for Elections and Democracy (Perludem). He attributes this issue to the single-day format, a consequence of a 2013 constitutional court decision synchronizing presidential and legislative elections.

In comparison to the previous 2019 elections, where almost 900 workers lost their lives, the death toll has decreased significantly. However, concerns persist, prompting election and democracy observers to advocate for further changes to alleviate the burden on workers.

This year saw over 5.7 million election workers serving at more than 820,000 polling stations across Indonesia, catering to 204.8 million eligible voters. Complex logistics and adverse weather conditions, such as flooding in Java, added to the challenges faced by election officials.

The deaths and illnesses are attributed to the unrelenting pace of the single-day format. Before 2019, presidential and legislative elections were conducted separately. Gadjah Mada University’s study after the 2019 elections revealed that Election Organising Team (KPPS) members worked an average of 20 to 22 hours on polling day. The absence of pauses in the voting and counting process, aimed at avoiding suspicion of fraud, further contributed to the physical and mental exhaustion of workers.

In response to the concerns, Indonesia’s health ministry conducted an evaluation and implemented changes since 2019. Health screening is now mandatory, and the age of election workers is capped at 55. The government, however, acknowledges there is room for improvement, particularly in health screening procedures.

Despite being provided with vitamins to endure the strenuous day, KPPS officers like Fahmi and Andri Maulana express dissatisfaction with the workload. Andri, stationed in Bekasi, West Java, worked from 7 am on February 14 until 9 am the next day, highlighting the physical toll and complexity of counting tasks.

The compensation for KPPS officers stands at IDR1.1 million to IDR1.2 million, with families of those who died receiving IDR36 million and funeral cost assistance of IDR10 million.

Experts, including Titi Anggraini of the University of Indonesia, propose a change in the election format to reduce the risks faced by KPPS officers. Issues such as late ballot paper arrivals and digitalization challenges during the counting process have added stress to an already demanding job. Titi and Heroik suggest holding presidential and parliamentary elections on the same day, with provincial, regency, and city-level elections scheduled two years apart, creating a more manageable workload for election officials.

While the single-day election model aims for effectiveness and efficiency, the current conditions risk the fatigue, illness, and death of officers, asserting the need for immediate reform in Indonesia’s electoral system.