10-9-2024 (NEW YORK) A groundbreaking study has revealed that the COVID-19 pandemic may have had a profound impact on adolescent brain development, particularly in girls. The research, conducted by scientists at the University of Washington, suggests that social isolation during lockdowns could have caused girls’ brains to age at a significantly faster rate than expected.

The study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, examined cortical thinning—a natural process that occurs during adolescence as the brain matures and becomes more efficient. Researchers compared brain scans taken before and after pandemic lockdowns in the United States.

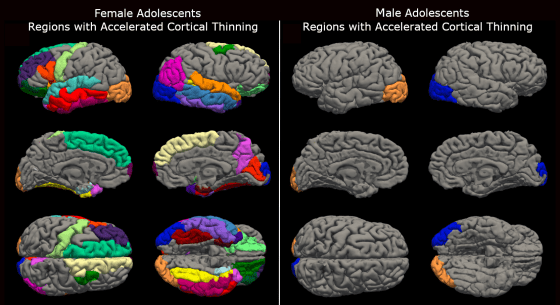

The findings were striking: while both boys and girls experienced accelerated cortical thinning, the effect was markedly more pronounced in girls. On average, girls’ brain development appeared to have advanced by 4.2 years beyond what was anticipated, compared to just 1.4 years in boys.

Dr Patricia K. Kuhl, a co-author of the study and director of the Institute for Learning and Brain Sciences at the University of Washington, described the disparity as “stunning”. She noted that a girl who was 11 years old at the start of the study might have returned at age 14 with a brain resembling that of an 18-year-old.

The researchers attribute this accelerated development to the social deprivation caused by pandemic restrictions. They hypothesise that adolescent girls, who typically rely more heavily on social interactions and verbal communication with peers to manage stress, may have been disproportionately affected by the isolation.

The study examined approximately 130 subjects, ranging from 9 to 17 years old, who underwent brain scans before and after the pandemic. The post-lockdown results were compared against a model predicting typical adolescent brain development.

Accelerated cortical thinning was observed across 30 different regions of girls’ brains, with particularly notable changes in areas associated with facial recognition, emotional processing, and language comprehension. In contrast, boys exhibited accelerated thinning in only two regions, both related to visual processing.

While these findings provide compelling physical evidence of the pandemic’s impact on adolescent well-being, experts caution against interpreting the results as definitively negative. Dr Ronald E. Dahl, director of the Institute of Human Development at the University of California, Berkeley, who was not involved in the study, emphasised that accelerated cortical thinning is not necessarily problematic and could be a sign of maturation.

The long-term implications of these changes remain unclear. Researchers are uncertain whether the accelerated development is permanent or if normal social interactions could restore typical rates of brain maturation.

This study adds a crucial dimension to the growing body of research on the pandemic’s effects on youth mental health. However, it also raises questions about the complex interplay between environmental factors and brain development during adolescence.