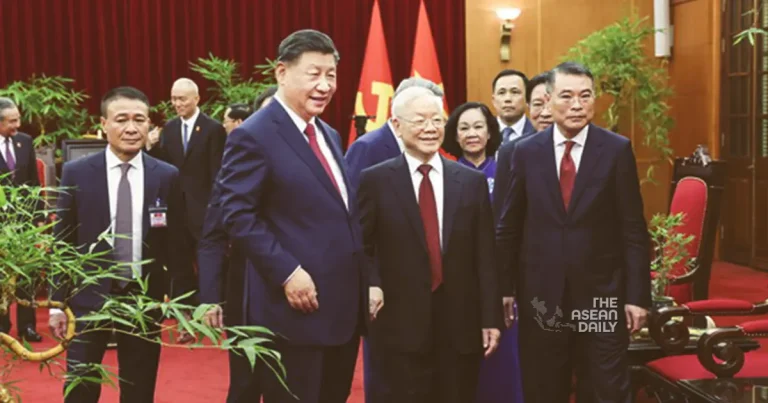

2-3-2024 (HANOI) Vietnam, once a country that operated in the shadows of global politics, is now in the spotlight as it garners attention from world leaders. US President Joe Biden and Chinese leader Xi Jinping both made visits to Vietnam last year, with the US elevating its relationship with the country to a “comprehensive strategic partnership.” Vietnam has also engaged in numerous free trade agreements and is sought after for collaboration on various issues such as climate change and supply chain resilience.

Despite these international partnerships, one thing remains unchanged: the Communist Party’s firm grip on power and control over political expression. Vietnam is one of the few remaining Communist, one-party states in the world, where political opposition is not permitted, and dissidents are regularly imprisoned. Decision-making within the party remains secretive.

However, a leaked internal document from Vietnam’s highest decision-making body, the Politburo of the Central Committee, has shed light on the party’s views on these international partnerships. Known as Directive 24, the document warns of the perceived threats to national security posed by “hostile and reactionary forces” that may enter Vietnam through its growing international ties. The directive raises concerns about the formation of civil society alliances, independent trade unions, and domestic political opposition groups.

Directive 24 urges party officials at all levels to counter these influences and highlights potential risks in areas such as the economy, finance, currency, foreign investment, energy, and labor. The document’s alarmist tone contrasts with the Vietnamese government’s usual public pronouncements, revealing a sense of insecurity. Human rights organizations, such as Project88, believe that Directive 24 signifies an intensified crackdown on human rights activists and civil society groups.

However, not everyone interprets the directive in the same manner. Some experts, like Carlyle Thayer, a renowned scholar on Vietnam, argue that Directive 24 reflects the party’s ongoing repression of activists rather than a new wave of internal repression. Thayer suggests that the timing of the directive, released after the US and Vietnam announced their elevated partnership, indicates the party’s concern about potential pro-democracy sentiments encouraged by the US.

The directive highlights the dilemma faced by Vietnam’s communist leaders as the country emerges as a global manufacturing and trading powerhouse. Unlike China, Vietnam cannot isolate itself behind a “great firewall” and relies on foreign investment and technology for rapid growth. Vietnam has agreed to various free trade deals, some of which include human and labor rights clauses. However, Directive 24 indicates reluctance to fully honor these clauses, particularly in relation to independent trade unions.

Critics argue that Directive 24 exposes the superficiality of Vietnam’s commitment to human and labor rights, suggesting that agreements with Western partners serve as mere fig leaves. They question which civil society groups will be allowed to monitor these agreements, especially given recent imprisonment of environmental and climate campaigners despite Vietnam’s energy transition partnership with Western governments.

As one-party Marxist-Leninist states become increasingly rare in today’s world, Vietnam’s leaders aim to maintain strict political control while exposing their people to foreign ideas and inspirations. They hope that this delicate balance will continue to fuel economic growth while preserving their grip on power.